- Updated 2022.7.12 16:54

- All Articles

-

member

icon

-

facebook

cursor

-

twitter

cursor

| |

|

|

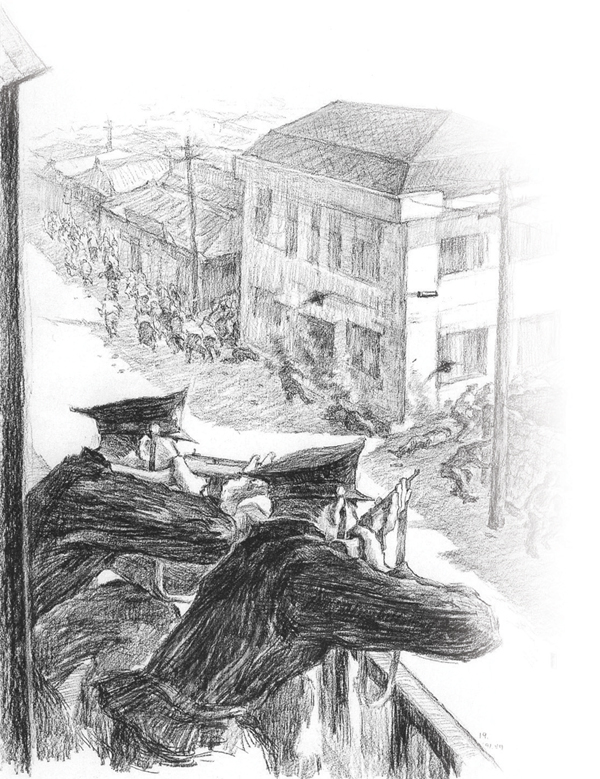

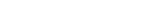

| ▲ Artist Kang Yo Bae’s depiction of the 1948 ‘shooting incident,’ sketched from the descriptions of witnesses. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

It was only after a lapse of 50 years that Jeju’s worst tragedy was openly unveiled at home and abroad. Before then, publicly discussing or addressing it was taboo or labeled as the suspicious acts of communists or leftists. Not until January 2000 when a Special Act was decreed by the Korean Government calling for an official investigation of the incident did a number exist of how many Jeju residents were massacred during the incident.

Most people know that this hauntingly beautiful island earned UNESCO World Natural Heritage status, but what fewer know is the fact that, after the 1950 Korean War, April 3, 1948, was the second largest massacre in Korea’s modern history. Scars of the onslaught are omnipresent on the island. Oreum seen everywhere on Jeju are not only secondary volcanic cones, but are often also the graveyard of many souls.

The April 3 Uprising, according to a statement released by the April 3rd Research Institute, was the “brutal suppression by the Korean government against armed rebellion in Jeju during the period of April 3, 1948, to Sept. 21, 1954.” Primary causes of the Jeju uprising, however, are a far more complex interplay of different factors - the Jeju people’s deep mistrust and anger toward government maladministration and Japanese police officers who abused their authority; co-stationing of the local and national army with a U.S. military presence; and a controversial looming election after the partition of the peninsula. In addition to that, lingering social unrest after the independence from Japanese rule was another cause of chaos in Jeju.

| |

|

|

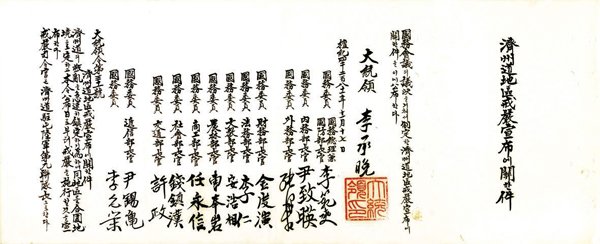

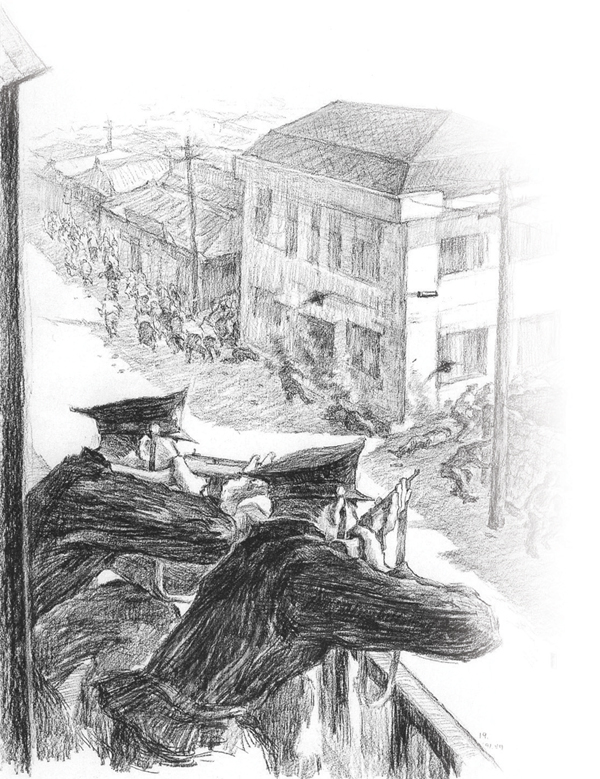

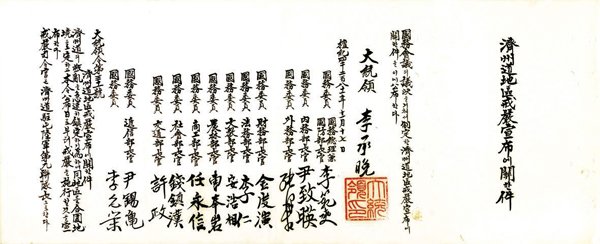

| ▲ The proclamation of martial law in order to quell the rebellion, issued by the Syngman Rhee regime on Nov. 17, 1948. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

An article titled “Jeju Island as the center for human rights and peace in the 21st century” in Peace Island, a magazine published by Institute of Peace Studies, depicted Jeju during that time as a society struck by “infectious diseases, years of famine, lack of basic foods, and a high unemployment rate” because of a sudden influx of refugees after liberation. All of these together boded ill for the future of Jeju Island.

Bruce Cumings, a professor at the University of Chicago who shed light on American involvement in the massacre, wrote that Jeju Island was unstable because “direct control of food rationing has also been placed in the hands of politicians responsive to Governor Yu Hae Jin, an extreme rightist.” Yu was known to be dictatorial in his dealing with opposing political parties and “unauthorized grain collections have been five times as high as official ones in 1947.”

Such political and social unrest continued to mount until it came to a head on March 1, 1947(*), (Korean Independence Movement Day) in what became known as the “shooting incident.” Not only were Jeju people commemorating the Korean struggle against Japanese rule, but they also planned rallies on March 1 to denounce the upcoming general elections scheduled for May 10, 1948. The elections were seen by Jeju residents as a unilateral attempt of the U.S. ruling government under the U.N. flag to separate a southern regime and to employ its first president Syngman Rhee.

| |

|

|

| ▲ Key U.S. and Korean military officers at a meeting in Jeju in May 1948. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

As the celebration at Gwandeokjeong, Jeju City, progressed, a batch of police officers from the mainland opened fire on the crowd, killing six and injuring eight people. Outraged, a group calling themselves the Jeju chapter of the South Korea Labor Party attacked police stations, burned polling centers for the upcoming election and attacked political opponents and their families. Imprisonments and a ruthless crackdown of the government on the left soon began, followed by torture which led to three deaths in prisons. An American investigator witnessed 35 prisoners crowded into a single 10 by 12 foot cell.

A series of general strikes of both private and state companies was staged to protest against both police oppression and the general election. Yang Jo Hoon, a leading 4.3 researcher and now a vice-governor of the Jeju provincial government, said, “The U.S. military rule administration concluded that Jeju was a red island on which most Jeju residents had leftist tendencies.” He continued, “Under U.S. military rule, Jeju Island, which protested against the government, was a thorn in the side.”

| |

|

|

| ▲ Bodies of massacre victims being unearthed and recorded after they were discovered in a mass grave near Jeju International Airport in 2008. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

At 2 a.m. on April 3, 1948, a full-scale uprising began. Rebels attacked police stations and government offices, killing an estimated 50 police. A cycle of terror and counter-terror soon developed. Police and rightists brutalized the islanders.

John Merrill, who in 1975 completed his master’s thesis on Jeju’s 4.3 massacre, wrote “nowhere else did such a violent outpouring of popular opposition to a postwar occupation.” The massacre was even described in The New York Times (Oct. 24, 2001) as “a campaign to cleanse ... any communist insurgents.”

Officially 39,285 homes were demolished and more than half of the island’s villages destroyed, concentrated mostly around Halla Mountain. Of 400 villages, only 170 remained. According to a report by the National Commission on the Jeju April 3 Incident, 25,000 to 30,000 people were killed or simply vanished, with upwards of 4,000 more fleeing to Japan as the government sought to quell the uprising. As the island’s population was at most 300,000 at the time, the official toll was one-tenth of the inhabitants. However, some Jeju people claim that as many as 40,000 islanders were killed in the suppression. This clash led to many deaths of U.S. military personnel, Korean police and right-wing youth alliance members, as well as the guerillas and civilians who were branded as traitors and sympathizers.

| |

|

|

| ▲ President Kim Dae Jung signing the 4.3 Special Law, authorizing an official investigation into the incident. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

In January 2000, more than 50 years after the tragedy, a Special Law was passed, requiring the government to look into the truth of the 4.3 incident. Efforts have been made since then to reassess the scope of the onslaught, compensate casualties and bereaved families, and restore the honor of the 4.3 victims. In October 2003, President Roh Moo-hyun apologized on behalf of the national government to the Jeju people for the April 3 Incident, stating, “Due to wrongful decisions of the government, many innocent people of Jeju suffered many casualties and destruction of their homes.” Roh continued, “To those people who died innocently, I pay respect and pray for their souls.” It was the first time an incumbent president had made an official apology for the 1948 massacre.

The residents of Jeju Island, now newly branded as “The Island of World Peace,” still mourn as the anniversary of the 4.3 Uprising draws nearer, but recognize that it is time to move on.

| |

|

|

| ▲ President Roh Moo-hyun apologizing to Jeju residents on behalf of the government for the incident. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

(*) An earlier version of this article misstated the date as 1948. It was 1947. The Weekly regrets the error.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ⓒ Jeju Weekly 2009 (http://www.jejuweekly.com)

All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published without the prior consent of Jeju Weekly. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U.S. Gen. Roberts, center, back, commanded the operation in Jeju. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

|

|

|

|

|

| A memorial to those acknowledged as missing. Image courtesy Yang Jo Hoon |

|

|

|

| Jeju-Asia's No.1 for Cruise |

|

|

|

Mail to editor@jejuweekly.com | Phone: +82-64-724-7776 Fax: +82-64-724-7796

#505 jeju Venture Maru Bldg,217 Jungangro(Ido-2 dong), Jeju-si, Korea, 690-827

Registration Number: Jeju Da 01093 | Date of Registration: November 20, 2008 | Publisher: Hee Tak Ko | Youth policy: Hee Tak Ko

Copyright ⓒ 2009 All materials on this site are protected under the Korean Copyright Law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published

without the prior consent of jeju weekly.com.

|